Technical Documentation as Code

I was 10 years old when I first touched a computer. A micro-computer, as we used to say. It was a PC Intel 386, installed at the travel agency where my sister used to work. She operated it to write texts and spreadsheets, nothing more. It was just a modern typewriter. At that time, there was no internet but computers were not that boring because it was new, different from everything I used to play.

I was there when she was not using it, fascinated with a text processor called Word Perfect, from Corel. In my opinion as a curious kid, it was better than Microsoft Word. My favorite task was typing touristic brochures into Word Perfect documents, just for the sake of typing. No games, no calculations, just text. I saved my files in a flop disk my sister gave me, put it into my backpack and headed home with my parents. Then I was back the next day to continue typing during the hype of the addiction.

At that time, most of personal and small business computing use was for writing with the primary intention to print the document and do some off-line work with it. Nowadays, the enormous amount of content published on the internet shows that printing is not a priority anymore. Most documents are less complex than before, with less formatting and variations to make them more accessible for a larger audience. The basic text formatting of HTML, far simpler than Microsoft Word, has shown to be effective to scale reading.

HTML-based content has been widely accepted and new technologies have been created, such as Markdown, Asciidoc, reStructuredText, and others, to rival with traditional office suites. These technologies are based on plain text with a minimalist syntax, easy to memorize. Their plain text model has been proven viable with the success of LaTex in the scientific world for decades. This kind of format is largely used for technical writing these days.

Markdown is the simplest and most popular format. I use it to write this blog and the experience has been better than my previous Wordpress version. Now, my texts are cleaner, well formatted and standardized after days migrating the messy content managed by Wordpress to the elegant and efficient Jekyll. On the other hand, the simplicity of Markdown is also its biggest weakness. It doesn’t cover all formatting possibilities of HTML. If you need something more elaborate, you have to embed HTML into your Markdown content. Technical people are ok with that, but HTML is too verbose and confusing for everyone else, which makes Asciidoc and reStructuredText more suitable options. They all have the HTML text formatting covered. I would personally pick Asciidoc because reStructuredText is very extensible to the point where the text and the extensions become highly coupled and we are forced to distribute both to have the text properly rendered by multiple writers.

Asciidoc for Technical Documentation

In principle, everyone who works with software has some notion of code. Programming languages have symbols to represent abstractions in a more succinct way, but Asciidoc is not considered a programming language because it is not Turing Complete. However, it is considered a markup language, just like HTML, with many symbols to hide complex abstractions. Therefore, it isn’t strange for people in a technical environment to adopt a language for technical documentation.

It is indeed time to try something new. Maybe, the use of word processors for technical documentation is the reason why the documentation is abandoned after some time. Despite their facilities, a single document cannot be edited by several people at the same time. There are ways to enable simultaneous collaboration in a single document, using Google Docs for example, but it’s difficult to assess the content and the quality of the contributions when people can change any part of the document at the same time. Whom to watch? What are they doing right now? Where? If I disagree, should I modify it myself or ask them to do it? Are they going to be notified? What if contributions are not related to the version that is about to be released, but related to a future release? How to produce different versions of the same document?

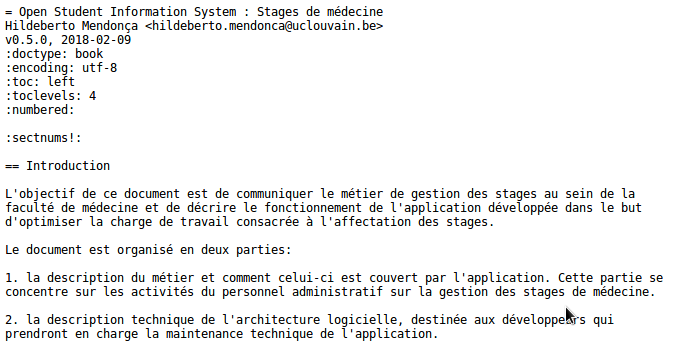

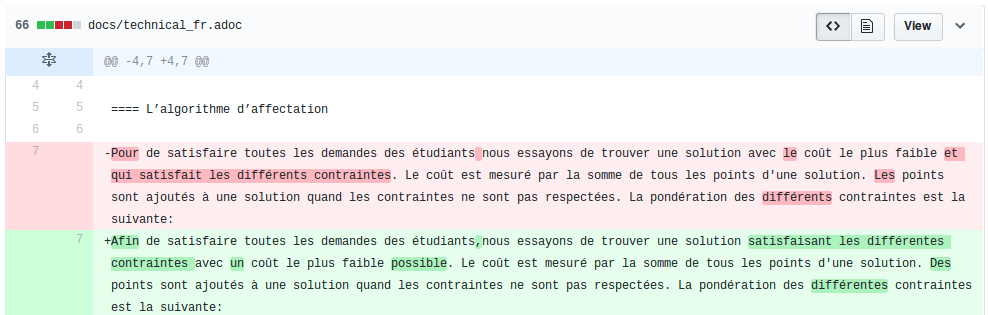

Documentation as code comes to the rescue! Using Asciidoc, a raw text format, writers can concentrate on content and leave presentation aspects for later. Raw text is also used by programming languages, making it the best format for versioning and sharing. The simple decision to manage documentation in a Distributed Source Control Management (SCM), like Git or Mercurial, can scale contributions from the entire company or even the entire planet! This is possible because writers work on their own version of the documentation and push their contributions to a central node when they are done. Contributions are not immediately merged to the trunk. They stay in an intermediary state, a merge request (pull request, as popularized by GitHub), where discussions may continue until reaching a point of maturity for the final merge. SCMs have astonishing merging capabilities, simplifying the work to a single click of a button.

In addition to scaling contributions, documentation as code may offer some additional advantages:

-

It detaches the documentation from tools, allowing you to chose the best set of tools to support your workflow.

-

The large majority of tools are free and open source, considerably reducing the cost of documentation.

-

Using raw text instead of binary, allows easy visualization of changes at the character level.

-

It is always possible to know who changed what and when.

-

It is possible to create branches aligned with the releases of a product, so you don’t deliver a documentation with more features than the recently released product just because you decided to advance the documentation of the upcoming release.

-

By using Asciidoc, a single content can be exported to several formats such as PDF, HTML, ePub, mobi and others.

-

Asciidoc also allows composition of files to form a document. This way you can share content among different documents, remove parts for a simpler version of the product, and many other possibilities.

Installing and Using Asciidoctor

Asciidoctor is a tool that recognizes Asciidoc files and converts it to HTML and other formats. It is written in Ruby, so you need Ruby installed to be able to run Asciidoctor. In my previous post, I explained how to install Ruby for development purposes. Please, follow the instructions there and come back here to install Asciidoctor and its PDF generator:

$ gem install asciidoctor

$ gem install asciidoctor-pdf --pre

Once installed, the commands asciidoctor and asciidoctor-pdf become available in the terminal. Their basic parameter is the Asciidoc file:

$ asciidoctor asciidoc-file.adoc

$ asciidoctor-pdf asciidoc-file.adoc

Documentation as Important as Code

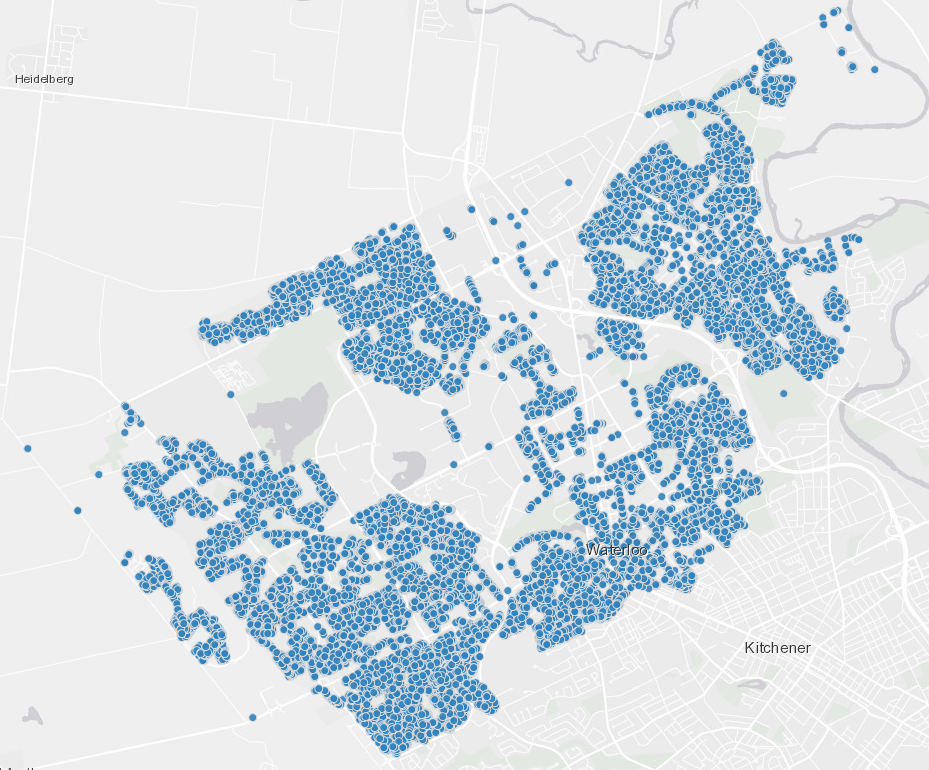

Asciidoc has been used in the OSIS Project since the beginning. It was well accepted by the team and a great deal of content has been produced so far. The main challenge we had was teaching distributed version control to non-technical people. It is still a challenge for some people, but it’s improving gradually.

I personally plan to document as code using Asciidoc in all my future projects and evangelize the concept from now on. After OSIS, I had the pleasure to document the OSIS-Internship module and it was very positive for the success of the project. It was hard at the beginning to produce the initial documentation because the module didn’t have any documentation at all, but after the first complete draft, small additions were actually easy to do.

My ultimate challenge is to convince other developers that documentation is as important as the code itself, because it ensures long term maintenance and the longevity of the project. But this is a subject for another time.

Recent Posts

Can We Trust Marathon Pacers?

Introducing LibRunner

Clojure Books in the Toronto Public Library

Once Upon a Time in Russia

FHIR: A Standard For Healthcare Data Interoperability

First Release of CSVSource

Astonishing Carl Sagan's Predictions Published in 1995

Making a Configurable Go App

Dealing With Pressure Outside of the Workplace

Reacting to File Changes Using the Observer Design Pattern in Go

Provisioning Azure Functions Using Terraform

Taking Advantage of the Adapter Design Pattern

Applying The Adapter Design Pattern To Decouple Libraries From Go Apps

Using Goroutines to Search Prices in Parallel

Applying the Strategy Pattern to Get Prices from Different Sources in Go