Can We Trust Marathon Pacers?

A pacer is an experienced runner that commits to other runners to run a race or a section of it in a predefined duration or speed. They also help with mental support for those who are struggling to stay out of their comfort zone. Many races have pacers, but not all. The ones that have attracted many runners looking for some help with their personal goals, like getting a new personal best, finishing a marathon under 4 hours, or even qualifying for Boston. But can we fully trust them to deliver what they committed to?

Pacers are human beings like every other runner. They can make mistakes, get injured, get tired, and so many other unforeseen situations. When we decide to follow a pacer we have to accept that anything can happen in such a long course, which might result in glory or frustration. It is about accepting a variable we can’t control. I had a personal experience with a pacer who was going faster than the average pace for the goal time. Most of my fuel was burned in the first half of the course, leaving me exhausted in the second half.

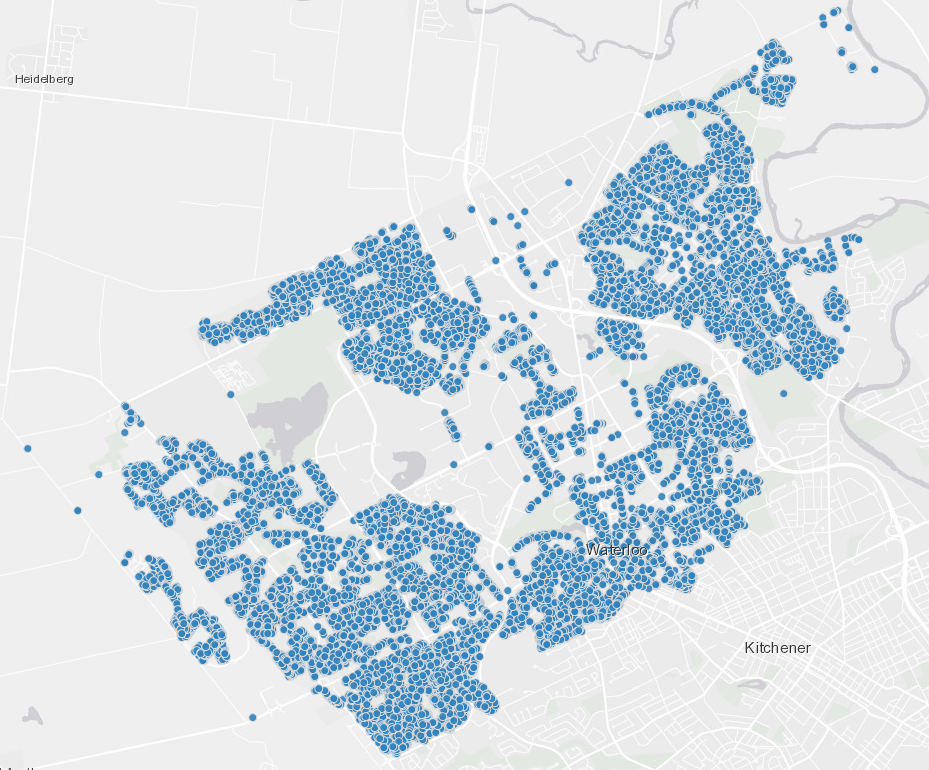

Let’s use LibRunner to investigate the case. If you are not familiar with LibRunner yet, read [an introduction we published previously] to learn how to run the following code. As published in Strava, the 4:10h pacer of the Calgary Marathon 2023 was running too fast for more than 30 km. But first, what is the average pace we would expect from him to finish the marathon in 4:10 hours?

use librunner::running::{Race, MetricRace, ImperialRace, Running, MetricRunning, ImperialRunning};

use librunner::utils::converter;

use librunner::utils::formatter;

fn main() {

const MARATHON_DISTANCE: u64 = 42195; // meters

let duration = converter::to_duration(4, 10, 0);

let marathon: MetricRace = Race::new(MARATHON_DISTANCE);

let running: MetricRunning = Running::new(duration);

println!("The pace to run a marathon in {}h is {}/km",

formatter::format_duration(running.duration()),

formatter::format_duration(running.average_pace(&marathon)));

}

It prints: “The pace to run a marathon in 04:10:00h is 05:55/km”. Looking at his splits, he was mostly below this pace and only slowed down in the last 8 km to the finish line. So, what was his average pace before he slowed down? Adding to the previous code:

let mut splits: Vec<Duration> = Vec::new();

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 53)); // 1km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 38)); // 2km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 44)); // 3km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 37)); // 4km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 29)); // 5km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 43)); // 6km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 33)); // 7km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 46)); // 8km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 30)); // 9km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 33)); // 10km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 27)); // 11km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 33)); // 12km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 37)); // 13km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 25)); // 14km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 42)); // 15km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 54)); // 16km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 42)); // 17km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 41)); // 18km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 50)); // 19km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 51)); // 20km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 43)); // 21km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 39)); // 22km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 43)); // 23km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 37)); // 24km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 42)); // 25km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 43)); // 26km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 42)); // 27km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 41)); // 28km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 36)); // 29km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 37)); // 30km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 34)); // 31km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 40)); // 32km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 47)); // 33km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 41)); // 34km

splits.push(converter::to_duration(0, 5, 51)); // 35km

let race: MetricRace = Race::new_from_splits(&splits);

let race_running: MetricRunning = Running::new_from_splits(&splits);

println!("The average pace of these {} splits is {}/km",

race.num_splits(),

formatter::format_duration(race.average_pace()));

}

It prints: “The average pace of these 35 splits is 5:39/km”. This is 16 seconds faster splits! What would be the finishing time if the pacer decided to maintain that pace until the end of the race? Adding to the previous code:

let faster_marathon: MetricRace =

Race::new_from_pace(MARATHON_DISTANCE,

race.average_pace());

println!("If he continued with the pace of {}/km to the finish line, \

he would finish the marathon in {} hours.",

formatter::format_duration(faster_marathon.average_pace()),

formatter::format_duration(faster_marathon.duration()));

}

It prints: “If he continued with the pace of 05:39/km to the finish line, he would finish the marathon in 03:59:06 hours”. This is almost 11 minutes faster! When runners are moving faster than what they trained for, they will hit the wall between 30 to 35 km, which is when their glycogen stores deplete. Therefore, any runner following that pacer would likely hit the wall and finish behind their initial goal.

Effectively balancing the energy consumption throughout the race, considering the elevation profile, and managing hydration and nutrition, definitely makes the marathon a strategic distance. We can have our strategy when we learn how our bodies perform under pressure or we can follow somebody else’s strategy, taking the risk of going off rails.

It is not about trusting a marathon pacer. It is about controlling as many variables as possible and being able to reason during the race whether it is a good idea to follow a pacer or not. For more tips on how to have more control over your pace, read this article published in Canada Running Magazine.

Recent Posts

Introducing LibRunner

Clojure Books in the Toronto Public Library

Once Upon a Time in Russia

FHIR: A Standard For Healthcare Data Interoperability

First Release of CSVSource

Astonishing Carl Sagan's Predictions Published in 1995

Making a Configurable Go App

Dealing With Pressure Outside of the Workplace

Reacting to File Changes Using the Observer Design Pattern in Go

Provisioning Azure Functions Using Terraform

Taking Advantage of the Adapter Design Pattern

Applying The Adapter Design Pattern To Decouple Libraries From Go Apps

Using Goroutines to Search Prices in Parallel

Applying the Strategy Pattern to Get Prices from Different Sources in Go